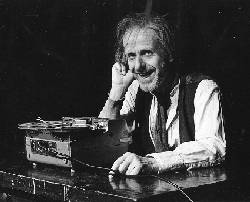

Julian Curry in Krapp's Last Tape

(photo by Porter Abbott,

Beckett Endpage) |

|

In Krapp's Last Tape, Beckett's aging protagonist plays back and

reflects upon his own tape recorded monologue from 30 years past. Tenses are

blurred here in a new way. The on-stage tape recorder challenges theater's

traditional use of staging conventions to denote the past, a practice that

itself is a form of fiction, since all theatrical action really takes place

in the present. This use of modern technology to mix past and present in one

tableau is unprecedented in theater. Further complicating the temporal

relationships is Beckett's indication that the play takes place "in the

future".

Video has a similar capacity for ambiguity through its ability to mix

live and recorded signals, a capacity that has been exploited by a long

series of video installations beginning with Frank Gillette and Ira

Schneider's Wipe Cycle, which combines live camera feeds (of the

installation's audience) with delayed feeds and prerecorded images. I am

also reminded of Krapp's Last Tape by Ken Kobland's film

The Communists are Comfortable, in which Spalding Gray's videotaped

monologue is shown on an old television set placed inside a living room set.

The entire room, including the TV, is filmed from a fixed wide angle. The

shot lasts for several minutes during which nothing happens away from the TV

screen. In 1996 Mike Taylor used a similar concept in an intermedia piece

she conceived for 77 Hz called Dangerous

Moonlight. For this work, we built a miniature set of an empty room with

a door at one end. Behind the half-open door was a rear-projection video

screen which displayed images from 1950s noir movies. The set was

rephotographed by a video camera and mixed with live images of an actor.

This in turn was processed in real time to resemble an old black and white

television broadcast. The resulting composite of past and present was

displayed to the audience on video monitors.

Minimalism, by avoiding the closure of completeness or comprehensiveness,

is quintessential open-system thinking. And the parallels between Beckett

and minimalist cinema are unmistakable. In Breath, Beckett's shortest

play, the curtain opens and closes on a stage occupied only by dimly lit

garbage. There is no action, and no sound except a faint offstage cry and a

single amplified human breath. The static tableau in cinema is of obvious

importance over the past few decades: think of virtually any piece by Bill

Viola, for example.

Beckett's work is notable for the frequent disparity between the visual

and aural rate of information. At one extreme are his wordless plays (Act

Without Words I and II, Quad, etc.), which can be

approached from the tradition of mime and dumb plays. At the other extreme

are plays that feature extensive monologue or dialogue, but virtually no

staged action at all. A good example is That Time, in which a spotlit

face is seen listening to its own voice emanating via loudspeaker from

different points in the auditorium. The face itself never speaks, and its

stage directions consist solely of blinking, breathing audibly and, at the

very end, smiling. A cinematic counterpart to this is Mike Hoolboom's

wonderful film The White Museum, which begins with 28 minutes of

white leader accompanied by a sound collage dominated by a voice-over, and

ends with a 7-minute high contrast black and white shot of a forest

accompanied by Mozart's Requiem. Another counterpart is Frampton's

Zorns Lemma, specifically its visually static but aurally complex

beginning and ending sections.

Beckett himself wrote several treatments for film and video. They have

received little consideration as models of experimental cinema, perhaps

because they are essentially photographed theater, shot in proscenium-style

sets (Film,

featuring Buster Keaton, is exceptional for using outdoor footage and a

fully enclosed interior set). Nevertheless, these works convey distinct

formal traits that have since become characteristic of the cinematic

avant-garde. Eh Joe, a television play written in 1965, resembles

That Time, since the only visible character, a middle-aged man, is

silent throughout. Virtually the entire film is spent on a gradually

tightening close-up of his face as sits on his bed listening to the faint

whispers of an unseen female voice. Although we are not told so in as many

words, the voice seems to be that of his dead wife. Periodically the voice

pauses, and Joe begins to fall asleep. As the camera moves closer, he is

reawakened by her resumed taunts. The process goes on without cutaways for

20 minutes. Finally, the voice becomes inaudible, and the picture slowly

fades to black. Eh Joe is not as long as Warhol's Sleep

(completed two years earlier), or Snow's Wavelength (completed two

years later), but the similarity is clear, and has not been generally

acknowledged in writings on early minimalist cinema. |