The Phantom of the Opera

Andrew Lloyd Webber, Charles Hart and Richard Stilgoe

"New Production"

Paramount Theatre,

Seattle (August 2018)

The touring "New Production" of The Phantom of the Opera, which originated in the UK in 2012, has just left Seattle. Yes, I went to see it. Yes, I know that the music is commercial, the story sentimental, and the acoustics of the local venue (the Paramount Theatre, built in 1928 as a vaudeville/movie house) ill-suited to a modern electrified musical. But however familiar Phantom has become through audio recordings, as well as the 2004 film adaptation and the 2011 25th anniversary production at Royal Albert Hall (the only theatrical version currently available on video), there's still value in seeing a big, complicated stage work like this in a live setting. Among other things, it helps to clarify the story arcs and disentangle which character sings which line. It allows a viewer to weigh the show's more visceral effects: its pyrotechnics, rotating set (deployed here in place of the less transportable scenery used in the West End and Broadway productions), and notorious tumbling chandelier (though the biggest theatrical catastrophe likely to befall Paramount attendees is the snaking line outside its inadequate women's restroom). Plus, seeing The Phantom anew in 2018 reinforces the role that it and other 1980s Euromusicals like Les Misérables and Miss Saigon had in establishing the trend on Broadway toward increased musicalization, as epitomized nowadays by shows like Hamilton where the music (sung, rapped and played as underscoring for onstage dialog) happens continuously.

A further, less expected perk was hearing Phantom in the pared-down tour arrangement (14 instrumentalists and a dedicated conductor), which makes an interesting contrast with the much larger orchestras used in the video versions and permanent productions. In general, the operatically-conceived styling of Phantom benefits from an enhanced string and wind complement. But some numbers, like the ballad All I Ask of You, heavy-handed to the point of bombast in its Royal Albert Hall guise, actually sound better with the more modest instrumentation of the touring troupe.

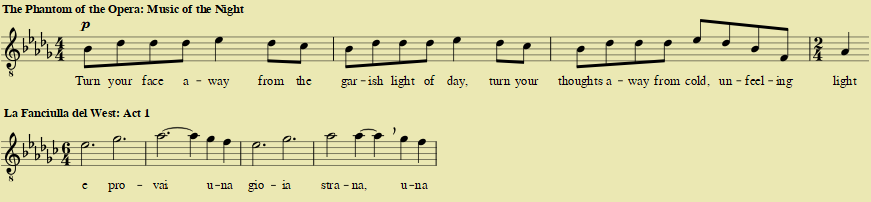

Moreover, I enjoyed the opportunity to reacquaint myself with a couple of points about The Phantom that I think remain undernoted, even after all these years—aspects beyond its crowd-pleasing patina that seem worthy of attention from those of us less sympathetic toward the multi-million dollar apex of popular music theater. One concerns the Puccini influence. Although much of the music in Phantom is rock-oriented, and the lively ensemble piece Notes is practically a Sondheim clone, the score is overall the most explicitly Puccini-esque of any musical that's survived its first production. Its lyric melodies and musical sentimentality, its leitmotifs, the lush orchestrations that emphasizes strings and woodwinds, are all quintessential Puccini traits. Yet commentators have tended to obsess over one specific detail: the resemblance of a single pentatonic phrase in Music of the Night to a similar tune from La fanciulla del West that's introduced by Johnson/Ramirrez in Act 1 ("and try a strange joy, a new peace, that I can't describe", sung in his characteristic key signature of six flats) and eventually reprised in the orchestra as Ramirrez and Minnie are released into exile at the end of the opera.

Despite drawing a legal challenge from the opportunistic Puccini estate, the similarity seems inadvertent to me, about as superficial as the "quote" from Beethoven's Ode to Joy in the finale of Brahms' First Symphony. More substantial, though less frequently cited, is the similarity between All I Ask of You and the recurring "love" motif in Fanciulla. Both melodies start with a downward leap, followed by an ascending arpeggio. Both are harmonized in a way that emphasizes 7th chords. And both are used dramatically to represent genuine romantic attraction:

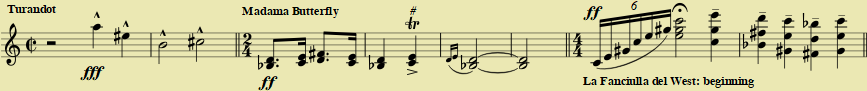

There's another borrowing in Phantom that relates to an common stylistic practice in Puccini: the use of whole tone scales to denote a lack of moral or social grounding. Examples include the first four notes of Turandot, the curse motif in Madama Butterfly and, again in Fanciulla, the music associated with Ramirrez throughout the first half of the opera, starting right with the prelude:

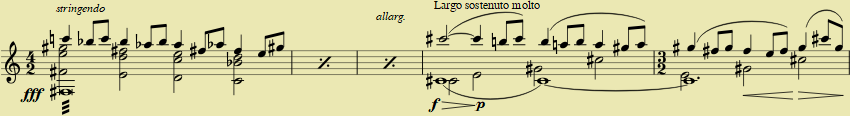

Since whole tone scales, like chromatic and octatonic scales, are symmetrical and lack a tonic (unlike major and minor scales, which are asymmetrical and include a clear leading-tone-to-tonic pattern), they're ideal for denoting an unrooted character: Turandot before she experiences love, Ciocio-san after abandoning her religion then being shunned by her family, Ramirrez while he's still a mendacious bandit. The latter case is particularly interesting in that the climactic scene in Act 2 where he and Minnie first kiss is accompanied by an orchestral passage that recalls the rolling whole tones from the prelude, but then transforms them into a C♯ minor diatonic pattern (at the Largo in the below example), thus confirming that Ramirrez has truly been redeemed by Minnie's love (Minnie, who is rooted morally and spiritually, is always associated with diatonic music):

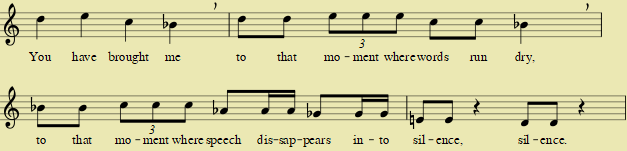

In Phantom, Lloyd Webber uses a four-note whole tone leitmotif (la ti sol fa) to represent Christine's longing for paternal love, her consequent emotional vulnerability, and the sinister exploitation thereof by the Phantom. The figure is first heard in Little Lotte, and it's especially prominent in Past the Point of No Return:

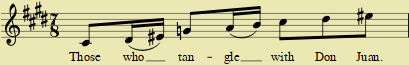

The leitmotif is usually accompanied by string-heavy block chords reminiscent of Vissi d'arte (this is more evident in the large cast recordings than in the reduced tour arrangement). Likewise, the music that the Phantom supplies for Don Juan Triumphant, the opera-within-an-opera, is itself loaded with whole tone material. In the rehearsal scene where Piangi, the company's hapless tenor, repeatedly botches a passage on the words "Those who tangle with Don Juan", the melody composed by the Phantom is an ascending whole tone scale, whereas Piangi keeps wanting to diatonicize it:

Which brings me to the other point. In the libretto's timeline, Don Juan Triumphant, derided by the company's suits and divas for its "ludicrous" scales, harmonies and time signatures, is receiving its premiere in the early 1880s. Musically it's years ahead of its time (Prélude à l'après-midi d'un faune and Also sprach Zarathustra were still more than a decade away). The Phantom isn't just a misfit, or a Hunchback that symbolizes every individual unjustly spurned by society—he's also a misunderstood visionary, a modern composer, a stand-in for every neglected, embittered artist accused of alienating the public. Could it be that the most apposite message embedded in The Phantom of the Opera—one of the most commercially remunerative musical plays ever, written by a composer frequently mocked as derivative—turns out to be a paean to uncompromised artistic integrity?

- Michael Schell (August 2018)

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2018 by Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.