Ives: Symphonies Nos. 3–4, The Unanswered Question, Central Park in the

Dark

Seattle Symphony, Ludovic Morlot

seattlesymphony.org, recorded 2015

Buy at Amazon.com

Has the bar been raised for Ives' 4th?

There's been a revival of Ives programming at Seattle Symphony lately. That it's happening under the French-born and British-educated Ludovic Morlot rather than his longstanding American predecessor Gerard Schwarz seems a bit ironic. But any initiative that can produce a decent recording of Ives' 4th Symphony is a good thing, and this CD, offered on Seattle Symphony's own media label, has the added distinction of being the first to use the new critical edition of the score. Published by Thomas Brodhead and his associates in 2011 (and viewable online here), it contains dozens of explanatory pages, restores many of Ives' footnotes that were omitted from the first edition, and clarifies numerous interpretive details such as tempo relationships between groups of musicians in the second movement, and how best to divvy up instruments in the first, second and fourth movements for spatial and rehearsal purposes. The result is an Ives' 4th experience that's still very familiar (nothing fundamental about the piece has changed) but has a hitherto unrealized degree of textural clarity.

Morlot conceives of the 4th Symphony as a grandiose piano concerto. There's indeed a "solo piano" part, prominent in the first two movements, and entrusted here to Cristina Valdés, who gets soloist credit on the CD (and during the 2015 live performances from which the CD was taken, she came onstage ahead of Morlot like a piano soloist would). It's also fair to point out that much of the second movement is basically an orchestration of the Hawthorne movement from the Concord Sonata. But there are many, many voices in the 4th Symphony, of which the solo piano is not even the only keyboard-based one: Ives calls for a second piano played by four hands, as well as a quarter-tone piano (nowadays rendered with two pianos tuned a quarter-tone apart). Additionally there's a celesta, a pipe organ (prominent in the fugue) and an optional ether organ. And Morlot uses a synthesizer for Ives' six octave "bells" part (the publisher even makes a carillon sample available for this purpose), thus comprising yet another putative keyboard instrument. Fortunately though, Valdés' part doesn't sound overbalanced in the mix, so any skepticism over the concerto conceit needn't worry us too much, especially when there are plenty of fresh orchestral details to be heard in this interpretation, for example:

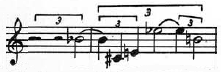

- In the second movement right after the first pass of the "celestial

train" dies down (at about 2:40), the violins play In the Sweet By

and By accompanied by some ppp arpeggios in the first

clarinet. These arpeggios usually get lost in the fray, but can be

clearly heard here:

- The "breakup" at the very end of the movement is more abrupt than most, reflecting the non rallentando marking in this edition of the score

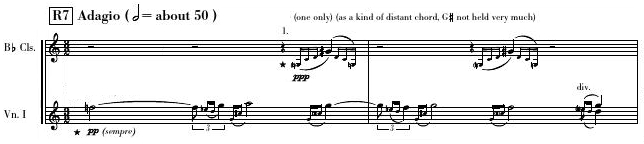

- The fourth movement starts with a statement of the seven-bar

percussion cycle that runs throughout its length. Usually it's played

siempre pianissimo, but the new edition restores a crescendo to

forte, then a diminuendo, in the middle of the cycle:

(Click on thumbnail

to expand image) - Later in this movement, a bit of fluttertonguing is added to the "thrush calls" in the high woodwinds as at 4:07 where they appear with the Distant Choir (four violins and a harp) recalled from the first movement. Brodhead points out that together, these instruments "complete the directive of the final measures of the third movement in which the trombone quotes from Joy To The World 'let heaven and nature sing...'"

- The separation between the percussion battery (L channel) and the Distant Choir (R channel) throughout the movement is better than in most recordings, though I personally would have appreciated an even wider stereo spread. At the live performances, these two groups were in the wings, each with their own conductor, but I think Ives would have preferred the use of some of Benaroya Hall's extensive balcony space. Ives even says "if the players are put as usual, grouped together on the same stage, the effect of the sound will not give the full meaning of the music"

There are parts of this symphony that I suspect reveal Ives' deep-seated, but repressed, doubts about God and the afterlife. The Distant Choir is one example. If you go to a Protestant prayer service, you won't hear real angels singing, and to the faithful that's not supposed to matter. But Ives so desperately wants to believe the angels exist, he explicitly writes them in. It's of a kind with the deeply personal nostalgia for an imagined America (as it "should have been") that pervades all of Ives' work. The doubt and the nostalgia distinguish Ives from a more credulous and straightforward mystic like Messiaen, who wrote his own angelic choir into the Quartet for the End of Time, but without the sense of doubt and loss, nor of any longing that a bit of heaven's perfection might descend earthward to improve the lives of the wretches still here. If Ives sounds more passionate and expressive than Messiaen, this internal dissonance must be one of the fundamental reasons.

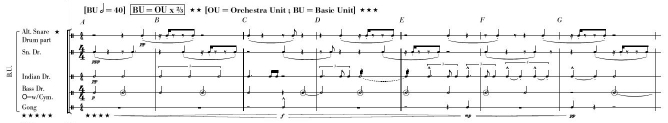

There's more though. The Unanswered Question is one of the Ives' most familiar and admired works. Because it's so familiar you might do a double-take when you hear it on Track 5. The CD booklet says the performance uses the 1934 Peermusic edition (which I believe was reprinted by Southern Music in 1953). This edition incorporates revisions that Ives made in his 50s whereby the recurring trumpet melody (which starts B♭-C♯-E-E♭) ends on either C or B♮:

But soloist David Gordon always ends the melody on the starting pitch, B♭. This would seem to correspond to Ives' original version, which is not what was published by Peermusic. Either way I find the finality of the B♭ less compelling and Ivesian than the "unresolved" C/B that we all know and love, but it's also possible that 40 years of hearing this piece the familiar way has made my ears a little inflexible. In addition to the trumpet line, the flute parts in this performance show numerous differences from what's published in the 1953 edition.

Next up is Central Park in the Dark, a marvelous and underrated tone poem, and a companion piece to The Unanswered Question. This time the repeating homophonic string "background" is atonal. And the melodic snippets played by the other instruments (of which the most conspicuous are the quotes from Hello Ma Baby) are tonal. In other words, it's the opposite scheme from that of The Unanswered Question. Central Park's string background is further remarkable for cycling through a chord progression that starts with stacked augmented triads, then goes to fourth chords, then mixed fourth chords then finally fifth chords before starting over:

The work ends atonally, in contrast with The Unanswered Question which ends in G major, thus explaining Leonard Bernstein's convenient omission of any mention of Central Park in the Dark in his Norton Lectures, which enlisted the tonal ending of The Unanswered Question as a metaphoric affirmation of the supremacy of tonal vs. atonal music.

I've less to say about Symphony No. 3, which represents Ives in his lyrical, pastoral mood. His scoring emphasizes the string choir, and the harmonies are lush and chromatic, though still tonal (and polytonal), throughout. The music is not far from what you often encounter in the violin sonatas, and some of the material, in the second movement especially, will remind you of General William Booth Enters Into Heaven. This recording includes the optional "distant church bells" (sampled in this case), a nice touch that's seldom employed.

The music in this album aptly demonstrates how Ives' polystylism and collage/quotation techniques delivered results that still sound fresh and relevant today, whereas works like Berio's Sinfonia and Bernstein's Mass now seem dated. I think Ives' customary reliance on abstract atonality as a substrate helps, as does the fact that he carefully chose his quoted material to construct an edifice of genuine personal authenticity, however dubious its historical accuracy. Like the world of Hollywood Westerns, Ives' sonic America owes more to its creator's imagination than it does to real history. But in both cases the constructed world is meaningful, coherent in vision, and recognizably American.

Seattle Symphony and Ludovic Morlot performing Ives: Symphony 4 by Brandon Patoc

The Seattle musicians, with the many augmenting choral and instrumental forces deployed in the 4th Symphony, sound wonderful here, even if there's the occasional bit of insecurity with things like quarter-tone intonation in the strings. With so much complexity to sift through, it's inevitable that some details will be sharper than others. But these musicians clearly enjoyed the challenge, and with the use of the 2011 edition thrown in, it seems likely that this 4th Symphony performance will rival Michael Tilson Thomas and the CSO as the reference recording for the piece going forward. About the only major shortcoming I can find with the album is the lackluster liner notes and inadequate coverage of editions and other textual details that are relevant to the 4th Symphony and The Unanswered Question. Otherwise this is a release that any Ivesian should rush to get. Might another Grammy be in the offing for this outfit?

- First published February 2016

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2016 by

Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.