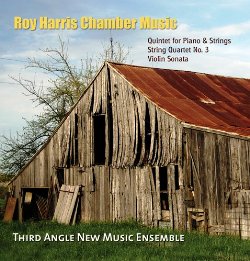

Roy Harris Chamber Music

Third Angle New Music Ensemble

Koch International Classics, released 2005

Amazon,

Spotify,

YouTube

Some highlights from the career of Roy Harris

Ah yes, the curious case of Roy Harris (1898–1979). Few composers in the Western art music tradition, and perhaps none from the US, have ascended the pedestal of public esteem so quickly, only to fall into such utter oblivion soon afterwards. Bursting into the limelight in 1939 with his Third Symphony, Harris's brand of neoclassicism—modal, broad-themed and open-textured—resonated with the Depression/WW2 era populist zeitgeist, fulfilling a nationalist longing for highbrow American orchestral music. A few quaint biographical details (like being born on Lincoln's Birthday to poor farmers in a log cabin in Oklahoma) reinforced his music's "pioneer" associations. And the advocacy of conductors like Koussevitzky during a period when commercial radio still had pretentions of disseminating high culture led to repeated performances and broadcasts. For a few tantalizing years he was America's most renowned living composer, and hardly a music history or orchestration textbook published in North America from WW2 through the 1980s failed to mention him.

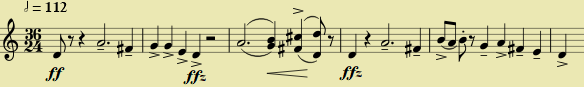

But celebrity is a fickle thing in America, and hindsight reveals that

Harris had benefitted from the lull between Gershwin's sudden death in 1937

and the ascendency of Copland's "Americana" masterpieces (Billy

the Kid, Rodeo, Appalachian Spring,

etc.). Copland soon usurped the All-American

Composer moniker, while the post-War dissemination of Ives' music led to the

latter's crowning as America's Greatest Symphonist. Meanwhile, Harris could

never recapture the magic of his Third Symphony, whose

fugue subject

(above) stands today as his only "hit tune". His inspiration flagged notably

from the 1950s onward, and though he remained productive and active in

academia into his old age, his music devolved into a kind of hackery

epitomized by the Bicentennial Symphony (1975–6), which

aptly demonstrates the dangers of Harris's style of harmonically static

modalism: At its best, the tension created by the continual eliding and

suspension of expected harmonic resolutions creates its own kind of

forward impetus. But when the invention is lacking, the music just seems to

be spinning its wheels. By the time Harris died in 1979, having tallied 14

symphonies in all, he was a marginalized and embittered figure, the Norma

Desmond of modern music.

Given all this baggage, Harris's reputation could

be ripe for a sober reassessment, and there are indeed many gems lurking

within his large and uneven output. This album by the Portland-based Third

Angle New Music Ensemble, recorded in 2001 and released in 2005, features

his two most important chamber works, both dating from his heyday in the

late 1930s.

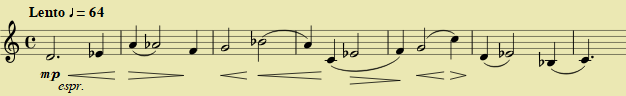

The Piano Quintet from 1936 (the dates listed on the album are inaccurate) is particularly interesting, the most important American work for this archaic ensemble between Bloch's Piano Quintet No. 1 (1923) and Feldman's Piano and String Quartet (1985). Ostensibly in three movements, it's built from a single axial melody that is treated first in a passacaglia, then as a series of solo cadenzas, and then transformed throughout the final movement, which is titled Fugue but which, typically of Harris, is more of a neoclassical invention with imitative entries. The gripping theme, which is stated first in octaves by the strings then harmonized in Harris's typically unorthodox fashion by the piano, coupled with the organic spinning out of the successive movements and episodes from this initial fount of material, make this the most compelling of all Harris's non-orchestral works.

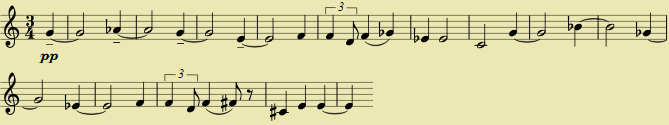

Next to be written was the String Quartet No. 3 (1937), which is cast as a series of four preludes and fugues. The latter, again, are rather free in their construction once the initial subject entries are accounted for. Parts of the Quartet approach the stylistic world of Bartók's contemporaneous Music for Strings, Percussion and Celesta (which begins with a rare example of a musically satisfying atonal fugue). Mainly though, the music stays within the more characteristic Harris sphere of model astringency, as with the third Fugue:

This is one of those works that often made it into modern counterpoint textbooks in North America, but are now rarely performed. Despite a tendency toward pedantry, it's still well worth a hearing.

Less remarkable is the Sonata for Violin and Piano (1942) which lacks the originality of the other two works, and occasionally lapses into vapid romanticism. Nevertheless it's given a solid performance here, as is the Piano Quintet, where the dynamic range and cumulative development of the central theme are emphasized. Less successful, I think, is the performance of the String Quartet, which should be more like Ives and less like Brahms. Its sudden transitions (as in the third Prelude, for example) should seem surprising, even jarring, the result of Harris's rhapsodic thinking, whereas this performance tends to rush through them in an attempt to maximize continuity. The sound engineering is spot-on throughout—just the right ambient distance from the sound sources.

I'm glad Koch has made this music readily available. If you're interested in 20th century music, then you ought to have Harris's Third Symphony in your library, perhaps along with the Seventh Symphony and the Violin Concerto. Complement that with this album, and you've got your essential Harris collection.

- First published February 2014, updated January 2019

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2014–19 by

Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.