A Tribute to Barbara Hammer: Making Movies out of Sex and Life

May 22, 2019

Northwest Film Forum

Co-presented with

Engauge

Experimental Film Festival

"My strategy…was to put a 'lesbian' body on the screen, to bring a lesbian subjectivity to film, to question heteronormative experimental film. This strategy worked for me but not always for lesbian audiences who hungered for representations with which they could identify in Hollywood-type narratives."

- Barbara Hammer (1939–2019) in Millennium Film Journal #51

Perhaps the most provocative thing about Barbara Hammer — author, feminist and inventor of lesbian cinema — was her relentless pursuit of an artistic vision whose integrity was personal, not simply political. That such an uncompromising approach, informed by the American tradition of experimental cinema, can pose a challenge to the assumptions of both sub- and mainstream cultures is confirmed by the experiences captured in her quote above, and by the modest audience of two dozen faithful who on May 22 gathered to honor her at Northwest Film Forum, smack in Seattle's Capitol Hill neighborhood, where crosswalks are painted in the colors of the rainbow flag.

The evening began with a brief reading from

HAMMER!, her

collection of autobiographical essays, then proceeded to a screening of two 16mm films made within

five years of each other that nevertheless present a remarkable contrast

in scope and technique.

Place Mattes (1987, 8', sound by Terry Setter)

Place Mattes was an obvious choice for the occasion, dating from a teaching stint at nearby Evergreen State College, and incorporating outdoor footage shot in the Pacific Northwest. The reference to cinematic traveling mattes is obvious to those familiar with optical printing (the technique is similar to greenscreen and video keying where one image is inserted within the outline of another). Here the outlines are Hammer's own hands and feet, shot in POV, and later expanded to include pointing arms and walking legs (but never her face). Unexpectedly, it's the foreground extremities rather than the backgrounds that are often overlaid.

Much of the footage is strobed, with a negative copy of the hands and feet trailing the primary image a few frames later as a kind of echo. Throughout the film, there's an ironic contrast of intimacy (the camera and extremities as an extension of the filmmaker and, vicariously, the viewer) and distancing (the hands and feet don't actually "touch" the keyed-in location footage). The visual style is quite representative of avant-garde cinema, but a bit unusual for Hammer in its G-rated imagery and generalized (not explicitly feminist) focus on personal discovery of places and emotions.

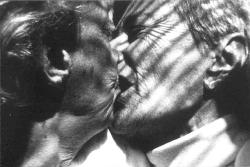

Stills from Nitrate Kisses

Nitrate Kisses (1992, 65')

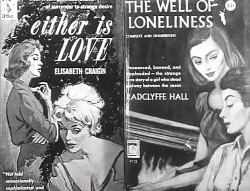

With Nitrate Kisses we slide to the opposite end of the Hammer spectrum, an hour-long commemoration of gay and lesbian voices from the WW2 generation. Voice-over narrations from same-sex couples are combined with referential musical excerpts in a manner typical of testimonial documentaries, the collage serving as context for the images, which are always black and white, thus projecting a sense of imperfect or forgotten memory. Hammer juxtaposes her own footage (including explicit scenes of the couples making love) with historical sources such as book covers from lesbian-themed pulp fiction and homoerotic silent movies.

Excerpt from Nitrate Kisses

The film is divided into three 20-minute sections followed by a brief epilogue. The first section begins with an intertitle quoting Adrienne Rich's Diving into the Wreck ("Whatever is…un-depicted…will become, not merely unspoken, but unspeakable") and focuses on the narrated memories of an American lesbian couple. One woman recalls the dance clubs on New York's Christopher Street, which catered to both men and women. If the police arrived for a vice raid, "we'd just switch partners". Cutaways of dilapidated houses (sometimes in negative) alternate with the lovemaking of two older women illuminated by sunlight entering their bedroom through blinds that cast linear shadows parallelling or intersecting the unclothed wrinkles.

The second section shifts the perspective to the generation's gay men. Again there's a focus on lovemaking, frequently intercut with Watson and Webber's 1933 film Lot in Sodom. One participant, a WW2 veteran, says "it's to two institutions, the US Navy and the Boy Scouts of America, that I owe everything", then goes on to fondly recall being seduced by a young Assistant Scoutmaster. Later he admits that "even the loss during WW2 didn't prepare me for" the AIDS epidemic. He poignantly touches on the film's underlying theme when he laments the impending loss (as of the early 1990s) of "many older men who are not out, who have wonderful stories to tell". In one sequence, grainy images of gay sex are accompanied by the "friendship" duet Dio, che nell’alma infondere' from Verdi's Don Carlo.

Section three highlights the experience of "asocial" (lesbian) women persecuted under the Nazi regime. Unlike their Jewish and Romani counterparts, surviving gay and lesbian people couldn't talk about why they had been in the camps. As if to suggest the persistence of taboos surrounding sexual "deviance" even amid evolving social acceptance, the principal lovemaking scenes in this section are of women in S&M attire. In a more droll stroke, these images are combined with the Act 1 love duet from Der Rosenkavalier, sung by two female voices, one of them a Hosenrolle.

The celebratory epilogue brings us fully into the film's "present day" with

scenes of a Pride gathering and a brief glimpse of Hammer's reflected face,

all underscoring the underlying plea to "the viewer, gay or straight, to save scraps, letters,

books, records and snapshots in order to preserve our ordinary lives as

history".

Perspective

That these two films remain compelling to us decades later testifies to their authentic striving for a new filmic identity. Hammer's work, at its best, conveys a sense of daring and speculation that contrasts sharply with the trendy, tendentious activist art so prodigiously produced in today's academically-connected channels. It seems apt that although Hammer herself taught and mentored at several universities, she remained wary of the conformist thinking that can beset such institutions. I recall her introducing Two Bad Daughters (1989, with Paula Levine) as "a corrective to the constipated state of feminist criticism", and indeed some of the bitterest screeds I've heard directed at her oeuvre have come from academic feminists.

But the strength of her work is precisely in its circumvention of gatekeepers old and new. At a time when the world is threatened by creeping tribalism and authoritarianism, Hammer's insistence on an affirming, individualistic kind of activism that is positive and self-actualizing offers an alternative to victimology, and an optimistic way forward.

- Michael Schell (first published May 2019)

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2019 by Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.