Alois Hába Centenary

Various artists

Supraphon, 3 CDs, recorded 1963–1987

Buy at Amazon.com

A historical curiosity for microtonality fans, worth a listen

There are a few composers that show up in the history books but whose music is rarely heard. Johann Stamitz is a typical case: father of the classical symphony, leading light of the Mannheim school, but nowadays totally eclipsed by the likes of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. Alois Hába, another Czech, gets into the 20th century music textbooks for his championing of microtonality, especially the quarter-tone scale. But few outside his homeland have actually heard any of his compositions. Because of this, I was glad to track down a copy of this Hába Centenary album, which I must take on faith represents as worthy an introduction to his work as you're likely to find.

There's a reason why Hába's music has had a limited impact: most of it is utterly neoclassical in all respects other than intonation. These three disks are crammed with sonatas, suites, string quartets and works with titles like Partita or Symphonic Poem. The music in general lacks the timbral invention and vernacular audacity of Partch (clearly the 20th century's most important microtonal composer), as well as the rhythmic and textural innovation of Bartók, Penderecki and Ligeti (who dabbled with quarter-tone tunings in several of their works). Most of these compositions are pitch-oriented, imitate traditional classical-romantic forms and rhythms, and remain stuck in 4/4 time (or another simple meter) throughout their duration. Think Honegger or Schoenberg with weird tunings, and you won't be too far off.

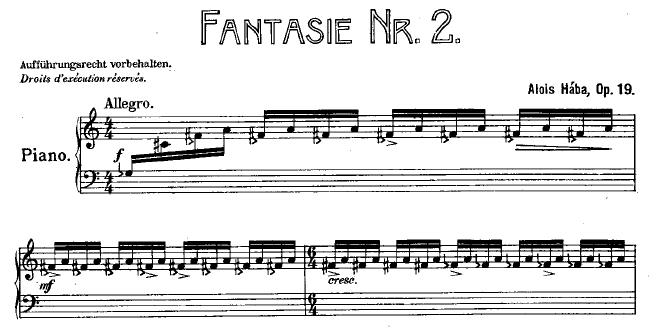

The string quartets that start off CD 1 are a good illustration of this "Hába dilemma". They use a variety of tuning systems ranging from conventional 12-tone equal temperament to quarter- and even fifth- and sixth-tones, but in other respects are fairly ordinary-sounding. Hába does a little better in the quarter-tone piano pieces on CD 2. Though they lack the invention and introspective genius of Ives' experiments in this genre, they manage to carry the implications of the tuning system beyond straightforward neoclassicism. The first movement of the Op. 88 Suite for quarter-tone piano, for example, exploits quarter-tone runs. It's not as dramatic as the near-glissandi from Partch's chromelodeon, but it's still striking if you haven't heard this sound before. The Suite's next movement emphasizes arpeggios built on a type of quartral harmony similar to Ives' Chorale (the last of his Three Quarter-Tone Pieces), but with a major third put in toward the top, reminiscent of guitar string tuning.

Quarter-tone piano constructed by August Förster to Hába's specifications in 1923

Hába seems to be at his most personal and inventive when writing for solo instruments. The Suite for Dulcimer (the hammered European variety similar to the Hungarian cimbalom, not the plucked Appalachian variety) is an interesting application of this instrument to the language of musical modernism. It may remind you of Stravinsky's atonal cimbalom in Reynard. Perhaps my favorite piece in the set is the Suite for solo cello, Op. 81b, whose creativity and contrasting movements rivals Britten's more familiar works in this form. Curiously, neither of these works depends on the impact of unusual tuning.

Score excerpt from Hába piano piece with quarter-tone notational indications

Disc 3 is devoted to orchestral music. The half-hour Symphonic Fantasy for piano and orchestra, Op. 8, dates from 1921, making it the earliest piece in this retrospective. It clearly shows the influence of the first wave of modernist orchestral masterworks: The Firebird, Bluebeard's Castle, Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra, etc. Curiously, in its line, form and rhythm it closely resembles the atonal but neoclassical works from Schoenberg's 12-tone period (which was still a couple years from being made public). Hába wasn't a twelve-tone composer per se, though he did tend to use equally sized pitch sets within a pretty regular metric structure, hence the resemblance. He embraced Schoenberg's emancipation of chromaticism and atonal harmony, but unfortunately also acquired Schoenberg's later propensity for rhythmic predictability. The Symphonic Fantasy is nevertheless a pretty ambitious and uncompromising piece, one that sees its soloist and a generally thickly-scored orchestra traversing a landscape of multiple sections at different tempos, often creating lively and compelling music. The overture to Hába's opera The New Land resembles the work of more generic second-tier modernists (e.g., Honegger), while The Way of Life, a tone poem on themes from anthroposophy (the spiritual philosophy of Rudolf Steiner, who founded the Waldorf schools) returns to the scale of Op. 8. Unfortunately Hába is at his most rhythmically monotonous here, and this along with the orchestration style makes me think of the kind of modernism that later became a commercial cliché (think of the underscoring to a 1970s television crime drama, or the ubiquitous high school wind ensemble compositions that flowed from the likes of Vincent Persichetti or Vaclav Nelhybel).

Bottom line

Hába was a competent but minor composer, so if you're new to 20th century music, you should definitely work your way through Debussy, Stravinsky, Ives, Varčse and the other giants long before you look here. Likewise, an exploration of 20th century microtonality should properly begin with Partch, not Hába. Nevertheless, this set is worth tracking down if you love modern music, or are curious about Hába or alternative tuning systems in general.

- Michael Schell

First published August 2010

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2010–16 by

Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.