Busoni: Doktor Faust

Philippe Jordan

Klaus Michael Grüber

Zurich Opera House, 2006

Blu-ray or

2 DVDs, Arthaus

Buy Blu-ray at Amazon.com

Buy

DVDs at Amazon.com

As musical innovators go, Busoni talked a great game. His little book from 1907, Sketch of a New Aesthetic of Music, was very forward-thinking and influential, and as a teacher Busoni mentored many progressive musical thinkers from Varèse to Grainger to Weill. Busoni's own music, though, has struggled to overcome a reputation as conservative and bland — neither as memorable as that of the great Romantic composers, nor as intriguingly original as that of the great modernists. Busoni has often been typecast into a kind of in-between stylistic ghetto analogous to that occupied by Janáček prior to his "discovery" in the 1960s. I myself carried this prejudice into my first encounter with Doktor Faust, whereupon I was delighted to discover that musically and dramatically it blows away any other major Busoni composition. It's still not at the level of Wozzeck, Oedipus Rex or Bluebeard's Castle, but given a sympathetic production it can hold its own with most other first-generation modernist operas.

Although Busoni was Italian, he lived much of his life in German-speaking countries, and Doktor Faust is set in that language. Busoni worked on the opera from 1916 through his death in 1924, and never finished the text nor the music for the work's ending. In Busoni's libretto, which he adapted himself from mostly pre-Goethe sources, the character Gretchen is marginalized (and indeed isn't heard at all), whereas we do encounter the Duke and Dutchess of Parma, the latter getting seduced by the magician Faust. The Dutchess dies, and Mephistopheles brings what purports to be their dead child to Faust, who immolates it causing a vision of Helen of Troy to appear from the ashes. Later, Faust realizes the emptiness of his life, and expecting to die at midnight, encounters a beggar (who he recognizes as the Dutchess) and a child. Through a last bit of magic and prayer, Faust transfers his life spirit to the child before dying. Some have criticized this libretto as rather shallow. And although there are two completed editions offered by two different musicians, there's still much conjecture about exactly what might have happened to the title character had Busoni been able to give him an authoritative denouement.

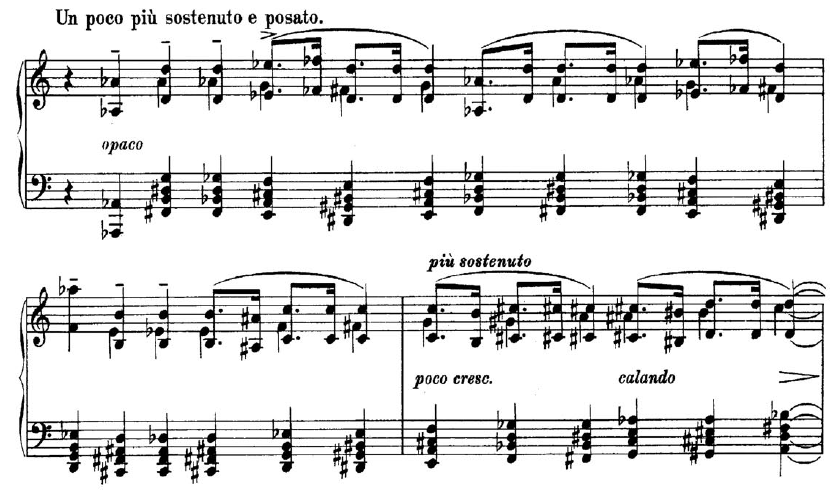

Musically the opera reflects Busoni's late, modernist-influenced style, and much of the music specifically reminds me of early Hindemith (the nattering student debate that opens the Wittenberg tavern scene could have come out of Cardillac). The processional music accompanying the gift of the magic book by the three "students" is drawn from Busoni's Piano Sonatina No. 2 (where it's written without a time signature), and it features some of the most dissonant, atonal chords in the composer's output:

The opera calls for the large orchestra typical of its time, including triple woodwinds, mallet instruments and organ. The latter instrument is featured prominently in the first intermezzo, which is set in a church (whose organist might as well have been Charles Ives, for the very chromatic and assertive solo supplied by Busoni). Orchestral players, along with choristers, are often positioned offstage and otherwise spatially distributed in elaborate ways, and this production actually used four conductors in total (though only Philippe Jordan is visible). As for the voice types, Busoni makes the "obvious" choice of a baritone for the title character. But the use of a tenor in the role of Mephistopheles is a great innovation: instead of the stereotypically deep and "sinister" bass voice you hear in Boito or Gounod, Busoni's devil is a conniving "whiny" character, sounding not all that different from Wagner's Mime (though without the latter's incompetence).

This production omits the spoken Prologue and Epilogue (though it still

clocks in just under three hours). It also uses, controversially, the older

Jarnach completion, rather than the newer Beaumont edition, which

significantly changes the ending, both dramatically and musically. In his bonus feature interview, conductor Jordan reveals that he prefers

the musically cumulative and "augmentative" effect of the Jarnach version. To hear

what you're missing, you should buy

Kent Nagano's 1998

recording, which gives you the option of either conclusion. As an aside, I

might mention Jossi Wieler's admired 2004 production for San Francisco Opera

which dispensed with completions altogether, leaving the ending ambiguous. Regardless of your feelings on the matter, the ending is musically stunning

in this production. Mephistopheles speaks the final line Sollte dieser Mann

etwa verunglückt sein? ("Could it be that this man has had an accident?").

Then the opera ends on perhaps the most colorful E♭ minor chord (or is it D♯

minor?) ever scored, its changing timbres suggesting that whatever Faust's

final attempts at good deeds, his ultimate end is non-redemptive.

This production omits the spoken Prologue and Epilogue (though it still

clocks in just under three hours). It also uses, controversially, the older

Jarnach completion, rather than the newer Beaumont edition, which

significantly changes the ending, both dramatically and musically. In his bonus feature interview, conductor Jordan reveals that he prefers

the musically cumulative and "augmentative" effect of the Jarnach version. To hear

what you're missing, you should buy

Kent Nagano's 1998

recording, which gives you the option of either conclusion. As an aside, I

might mention Jossi Wieler's admired 2004 production for San Francisco Opera

which dispensed with completions altogether, leaving the ending ambiguous. Regardless of your feelings on the matter, the ending is musically stunning

in this production. Mephistopheles speaks the final line Sollte dieser Mann

etwa verunglückt sein? ("Could it be that this man has had an accident?").

Then the opera ends on perhaps the most colorful E♭ minor chord (or is it D♯

minor?) ever scored, its changing timbres suggesting that whatever Faust's

final attempts at good deeds, his ultimate end is non-redemptive.

Any production of Doktor Faust revolves heavily around its two lead singers. Thomas Hampson has set the bar for the title role since 1999 and seems at home at Zurich, which turns out to be the base for his vocal coach Horst Günter. Though born and educated in America, Hampson is comfortable discussing the opera in German during his interview (the second of the two bonus tracks). As for Mephistopheles, tenor Gregory Kunde, another American, clearly relishes this unusual opportunity to play a high-voiced bad guy.

The recorded sound is quite good. I was pleasantly surprised with the balance between voices and orchestra. My only regret engineering-wise is that the orchestral sound is occasionally flat. In their defense, the technical crew had to deal with offstage choruses and offstage musicians (voices are always coming out of nowhere, Busoni emphasizing the supernatural), not to mention the large orchestra. The live footage from 2006 also reveals the admirable discipline of European opera audiences who allow the most delicate of scene endings to be heard (North American audiences would be applauding as soon as the horizontal curtains started to close).

In the history of musical adaptations of the Faust legend, Busoni's opera stands as an important bridge between the Romantic (in various senses!) endeavors of Berlioz, Gounod and Mahler (all followers of Goethe), and the less sentimental postmodern approaches of Schnittke, Pousseur, Dusapin and even Stan Brakhage in his Faustfilm: An Opera. At present, this Jordan/Grüber production is the only video representation available of this important but seldom mounted 20th century opera. Hats off to Arthaus for bringing it to us.

- Michael Schell (first published March 2015)

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2015–18 by

Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.