Berlioz: Beatrice & Benedict

February–March 2018

Seattle Opera

Conductor: Ludovic Morlot

Stage Director: John Langs

A new approach

The key thing to know about John Langs and Ludovic Morlot's new production at Seattle Opera is that it's not so much a mounting of Béatrice et Bénédict as it is a staging of Shakespeare's Much Ado About Nothing featuring lavish songs and orchestral music by Berlioz.

Left to its own devices, the opera Béatrice et Bénédict clocks in at a meager hour-and-a-half, including overtures, dances, 15 sung numbers and intervening dialog. To achieve this slim profile, Berlioz excised entire plot arcs from Shakespeare's original, most notably the connivances of the Iago-like character Don John, whose false witness causes Claudio to believe that his fiancée Hero has been unfaithful to him. Thus deceived, Claudio denounces Hero at their wedding, whereupon Hero's family fakes her grief-stricken death. Fortunately, an overheard conversation causes the truth to come out, and the lovers are eventually reconciled.

Having shorn Shakespeare's text of most of its drama, Berlioz's libretto comprises the courting machinations of one serious couple (Hero, whose arias now seem inexplicably melancholy, and Claudio, whose personality is largely neutered) and one comic couple (the opera's title characters, longtime frenemies who become lovers through the deceptions of their friends who eventually convince them of each other's affection). Tovey described the product as "Much Ado About Nothing without the Ado", and the opera has struggled to remain on the fringes of the repertory. The goal of Seattle Opera's production is to put the Ado back in.

Langs does this by restoring much of Shakespeare's text and by delivering the entire work in English. This extends its overall length to just over two hours, including several lengthy spoken scenes. The demands on the lead roles thus expand to include the ability to convincingly deliver spoken Shakespearian English. Happily both Daniela Mack and Alek Shrader, opera singers by trade, were up to the task on opening night. Other characters, missing entirely from Berlioz's score but restored here, are assigned to actors from the extended circle of ACT Theater in Seattle (where Langs is Artistic Director). Most important of these is the embittered conspirator Don John (played by Brandon O'Neill), who in his first expository scene is seen cruelly plucking the wings off a (mechanical) butterfly, and in subsequent appearances is shown hacking at onstage plants with his sword. Other restored acting roles are Don John's associate Borachio, Hero's attendant Margaret, and Friar Francis (a counterpart to Friar Lawrence in Romeo and Juliet). The spoken role of the watchman Dogberry has been combined with Shakespeare's sung role of Balthasar and Berlioz's sung role of Somarone (invented by the composer to serve as the chorus leader for an intentionally awkward onstage epithalamium early in the first act), the resulting composite comic role being assigned to bass Kevin Burdette. (Where Berlioz's text settings are retained, the creative team has retranslated his French lyrics — which according to Morlot read as a somewhat archaic-sounding word-for-word translation of Shakespeare — into English. At all other times, the English is Shakespeare's.)

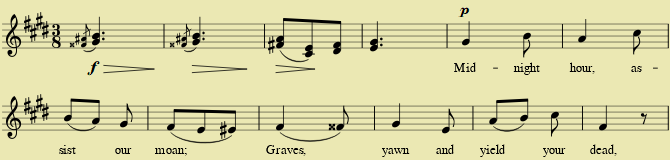

Where necessary, Morlot extracts and vamps orchestral excerpts as underscoring. Snippets from the Overture, for example, are brought back later to lend an ominous undertone to Don John and Borachio's schemings. In at least three places entire vocal numbers from other Berlioz works have been inserted, with Shakespeare's original lyrics adapted to Berlioz's rhythms by Jonathan Dean, Seattle Opera's resident dramaturge and supertitlist. The beginning of the second act, for example, is marked by an aria repurposed from Benvenuto Cellini and given to Claudio to express his anguish over Hero's perceived infidelities. Later on comes the more recognizable appropriation of the famous Shepard's Farewell from L'enfance du Christ as a choral setting of Shakespeare's lament for the (not really) dead Hero:

This approach moves the result closer to the dialog + musical number mix of American musical theater. I imagine it resembling one of those extravagant Romantic era Shakespeare productions for which Mendelssohn, Tchaikovsky and Sibelius wrote their incidental music (complete with brief cues, underscoring and other miscellaneous numbers usually omitted from concert performances). Think of Kiss Me, Kate with Berlioz instead of Cole Porter.

A single set served for both acts, built around flanking spiral staircases of the kind that have been familiar sights at Seattle Opera since its 2010 Lucia di Lammermoor. Connecting them was a maze of straight stairs and skyways creating a look reminiscent of Escher's famous illusory print Ascending and Descending. The costuming was likewise ambiguous: soldiers wore Napoleonic style military jackets and hats, while civilian men wore suits and hats that seemed to be out of the 1930s. Women wore long, archaic-looking dresses and skirts, but at other times sported tank tops. It all added up to a sense of things not being as they appeared — an apt counterpart to Shakespeare's themes of deception.

Photo: Jacob Lucas (Seattle Opera)

A nice stroke was placing the intermission right after Claudio witnesses Borachio being seduced by Hero (who is really Margaret in disguise, a sham engineered by Don John). Langs avoided the temptation to reference Berlioz's own personal life, which included an obsession with idealized Shakespearian female archetypes that culminated in his ill-advised marriage to actress Harriet Smithson.

And the music?

Though this production's theatrical novelties may overshadow thoughts on

the music itself, it's worth circling back for a bit to consider how Béatrice et Bénédict exemplifies

what's often called the

"Berlioz problem". There's general agreement that Berlioz was

among the 19th century's most intriguing musical mavericks — among other

things he was unique in writing both symphonies and operas but no piano or

chamber music. He is universally admired for his skill with the orchestra,

being the first of the modern conductor-composer archetypes, the author of an

orchestration treatise that's still in use, and the source of much of what we

have come to associate with the "Romantic sound", such as reliance on valved

brass, use of unconventional instrumental combinations, and sheer ensemble

size (Symphonie fantastique premiered

with an orchestra of about 130 musicians, though nowadays one gets by with

closer to 90). The quintessential French emphasis on orchestral

color originated with Berlioz, and has continued through Debussy, Ravel, Messiaen and Boulez

to contemporary composers such as Murail, Dusapin and Saariaho (the latter

officially Finnish but long based in France). Consensus seems to regard

Berlioz as the most important French composer between the Baroque era and

Debussy (keeping in mind that Franck was Belgian by our standards), but

still ranks him a rung or so below giants like Beethoven, Brahms, Verdi

and Wagner, even if he's customarily given an edge

over most of the Nationalists (Grieg, Smetana, Rimsky-Korsakov, etc.).

Beyond that, feelings about his music vary.

It's an odd mix of Romantic-era form and aesthetics with Classical-era harmony. Some people

enjoy his unpredictable colors and phrasing. Others feel

he lacked the melodic gift of a Tchaikovsky, the harmonic gift of a

Beethoven, and the dramatic gift of a Wagner. I

personally have struggled with the Beethovenesque complexity of form

supporting a sound surface dominated by an insistent and typically French

lyricism. And even his supporters acknowledge a certain unevenness to the

work, often within a single composition. The

overture to Béatrice et Bénédict, which has had a

life of its own in recordings and concert halls, displays this last

propensity. It begins promisingly enough, with a catchy mazurka-like tune that

seems curiously halting, full of hemiolas and grand pauses:

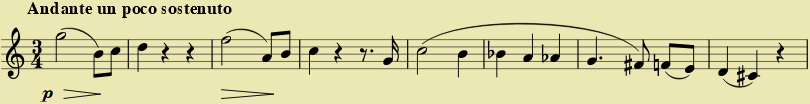

Alas, after a few bars the allegro abruptly stops, and we must endure a long slow passage based on one of Berlioz's less inspired melodies (taken from Beatrice's aria where she asks herself if she's really becoming attracted to Benedict):

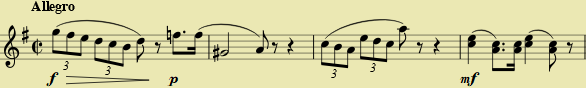

Finally the brisk tempo and snappy rhythms return, at which point we realize that we've hearing the exposition proper, and that the foregoing happenings have been introductory in function. We also realize that the time signature has changed to alla breve, and that the halting nature of the main theme's first appearance was due to its having been superposed on a triple meter, whereas its "real" meter is duple. The remainder of the overture is a conventional but jaunty and satisfying affair:

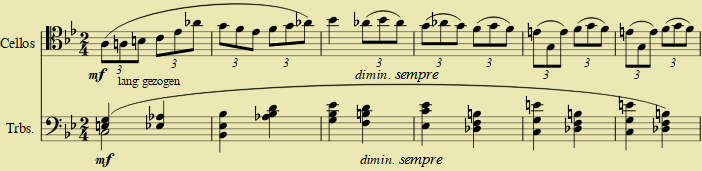

Berlioz's penchant for unusual scoring is revealed in a voice + brass aria from The Damnation of Faust that's sung in this production by Somarone using lyrics assigned by Shakespeare to Balthasar:

It anticipates this remarkable passage from the scherzo of Bruckner's Fourth Symphony, written 16 years later and scored for only cellos and trombones:

A match or not?

So, does presenting a Shakespeare comedy in English using an operetta format with Berlioz's music (originally intended for French diction) actually work? I'm maybe 80% confident that Langs, Morlot and Dean have pulled it off, but I'm 100% certain that the result is more interesting than a straight French language production of Béatrice et Bénédict in Seattle would have been. Presented as part of the Seattle Celebrates Shakespeare initiative, the production has received a delighted response from both Shakespearean theater types and regular opera-goers, leading to rumors about reassembling the creative team to tackle Gounod's Roméo et Juliette sometime in the future. It's definitely one of the most unusual Seattle Opera mainstage production to come along in quite some time.

- Michael Schell (first published March 2018)

Benedict eavesdrops on Claudio, Leonato and Don Pedro

Photo:

Tuffer (Seattle Opera)

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2018 by Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.