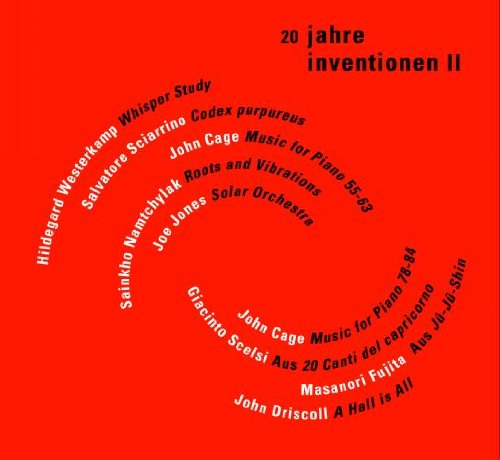

20 Jahre Inventionen II

Music by Westerkamp, Sciarrino, Cage, Namtchylak, Jones, Scelsi, Fujita and

Driscoll

Edition RZ, released 2003

Buy at Amazon.com

Interesting cross-section of avant-garde music from the late 20th century

From 1982 to 2010 the Inventionen festival was a fixture of Berlin's formidable contemporary music scene. For its 20th anniversary the festival released a series of audio documents including this CD, which is a grab bag of works presented between 1986 and 1994. Most "highlight" albums of this sort are of dubious curatorial quality, but this one rises above the fray, presenting samples from at least two musicians that are not well known in North America, and preserving some examples of installation/environmental sound works that are seldom captured well on CD.

First up is a piece from Hildegard Westerkamp, a German-Canadian artist best known for installation and composed environment works. Her fixed media piece Whisper Study is built from recorded footsteps, breaths, and the kinds of rapid, short, brittle-sounding timbral clouds characteristic of the nature-based sound art that was pioneered in North America (Leif Brush, Marianne Amacher, John Hudak, etc.) and eventually led to more commercial genres like ambient field recording. Amid the sound collage is the occasional voice of Westerkamp herself whispering snippets of poetry by her husband Norbert Ruebsaatg.

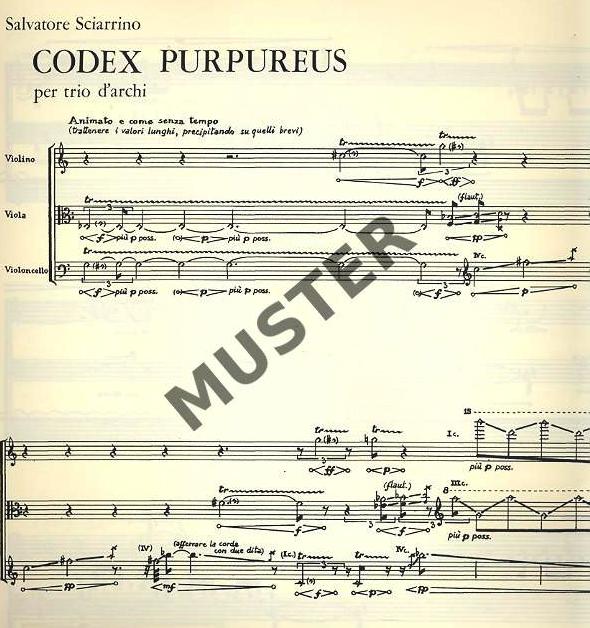

As I write this, Salvatore Sciarrino is considered by most of his colleagues to be Italy's most important living composer. His work takes Webern and Feldman as a starting point, cherishing the individual note or sound as an integral whole, and displaying an affinity for music that's very slow and very soft. Add in the indeterministic aesthetic of Cage, the fleeing gestures of Bartók in night music mode, and the sound world of the sonorist compositions of Ligeti, Penderecki and Xenakis, and you get the introverted milieu of Sciarrino — a style very close to that of Helmut Lachenmann. Sciarrino's Codex Purpureus is a miniature for string trio, entrusted here to members of the Arditti Quartet, who cherishingly coax gentle scratches, groans, glissandi, trills and tremolos from their instruments. Gestures and pitches are fleeting in this extreme nocturne. It's a fine introduction to his oeuvre, and a nice juxtaposition with the Westerkamp piece, whose sounds mainly come from nature but are often rhythmically similar to Sciarrino's.

Cage: Music for Piano

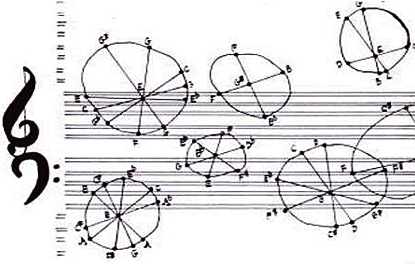

Speaking of Cage, he's represented by Music for Piano (from 1956), an important legacy piece whose presence in this collection underscores his importance in seeding both the American branch of post-Webern thinking and much of the European avant-garde from Darmstadt onward. The specific connection with the Italians Sciarrino and Scelsi is made obvious by juxtaposing their music with two excerpts from this piece, both performed by Herbert Henck. I've already mentioned Sciarrino. As for the maverick Giancinto Scelsi, his reputation in North America skyrocketed during the last decade of his life, buoyed by a wave of interest in microtonal music. I personally think that Scelsi's timbral sensibilities are best represented by his large ensemble works, such as Knox-Om-Pax. I haven't warmed to his solo and chamber music as much as some of my colleagues, and the two Songs from Capricorn — here performed by their dedicatee Michiko Hirayama accompanying herself on a Thai gong — seem rather slapdash compared to something like Ligeti's Aventures and Nouvelles Aventures.

The Tuvan singer Sainkho Namtchylak came to prominence in the 1990s with the concomitant exposure in the West of Tuvan and Mongolian folk music, which features the same overtone singing technique as the more formalized and better-known chant performed by certain schools of Tibetan Buddhist monks. Namtchylak has distinguished herself from other Tuvan musicians by combining her native tradition with everything from New Age and pop to the avant-garde tradition represented by Inventionen, and of course her voice's gender also sets her apart from the vast (male) majority of Central Asian throat singers. Here she's heard with two percussionists whose contributions are electronically processed and projected. The booklet credits the track as a Namtchylak composition called Roots and Vibrations, and provides a pamphlet poem penned by her that brings back memories of Sun Ra albums, but the music itself sounds very improvisatory to me.

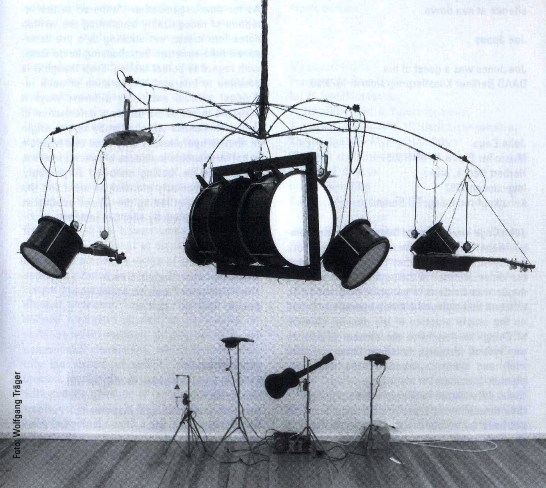

The Fluxus artist Joe Jones, not to be confused with drummer Philly Joe Jones, grew up in Brooklyn but spent most of his lamentably short adult life in Germany, building solar-powered "self-playing" instruments in the tradition of Trimpin and others. The surface intricacy of the (often percussive) sounds that he conjures up in his Solar Orchestra installation are, again, similar to the rhythms of the Westerkamp and Sciarrino pieces (and to the long percussion-only jam that concludes the Namtchylak track). This recording respectfully conveys the ambience and complexity of the environment Jones constructed for Inventionen 1990, and is to be particularly cherished since so little of his output is currently available in listenable form.

The last two tracks seem less successful. At 23 minutes, Masanori Fujita's Jū-Jū-Shin is the longest work on the album, even though what's presented here is a mere excerpt from a longer span. I admit to being unqualified to assimilate its Buddhist text (derived from the teachings of Kūkai, the Japanese monk responsible for the Shingon sect). And perhaps that's a fatal limitation. Fujita's composition is written for 15 Japanese monks who sing and play various percussion instruments. There's a thick layer of reverberation and what sound like electronic drones added in, but the liner notes are not clear on the instrumentation, and I'm not at all familiar with this composer's other works. Jū-Jū-Shin is pleasant enough to listen to, but it strikes me as derivative both of Buddhist ritual music traditions (Tibetan and Japanese) and of certain Western works composed under their influence (such as Stockhausen's Luzifers Abschied from 1982). The next and last track is a sample from John Driscoll rotating loudspeaker installation piece A Hall Is All. Driscoll is an alumnus of David Tudor's Rainforest project, and much of his work emphasizes phasing and sound projection of simple sound sources in a way reminiscent of Alvin Lucier. It's a genre that's seldom done justice by conventional stereo recordings, and the present case is no exception.

This CD isn't going to alter history like The Rite of Spring or the Darmstadt courses. But if you can find it at a reasonable price, perhaps in a propitiously timed visit to your favorite used CD store, then I trust you'll enjoy its unique mix of familiar and unfamiliar avant-gardisms from the not-too-distant past.

- Michael Schell

First published February 2016

![]()

Selected writings |

Schellsburg home

Jerry Hunt |

cribbage

![]()

Original Material and HTML Coding Copyright © 2016 by

Michael Schell. All Rights Reserved.